My heart was racing. My palms sweating. I was going to be fired.

Performance reviews had just ended, and it was time to meet my manager and be told my results. Except I knew what it would say. How else do you rate a programmer who doesn’t code?

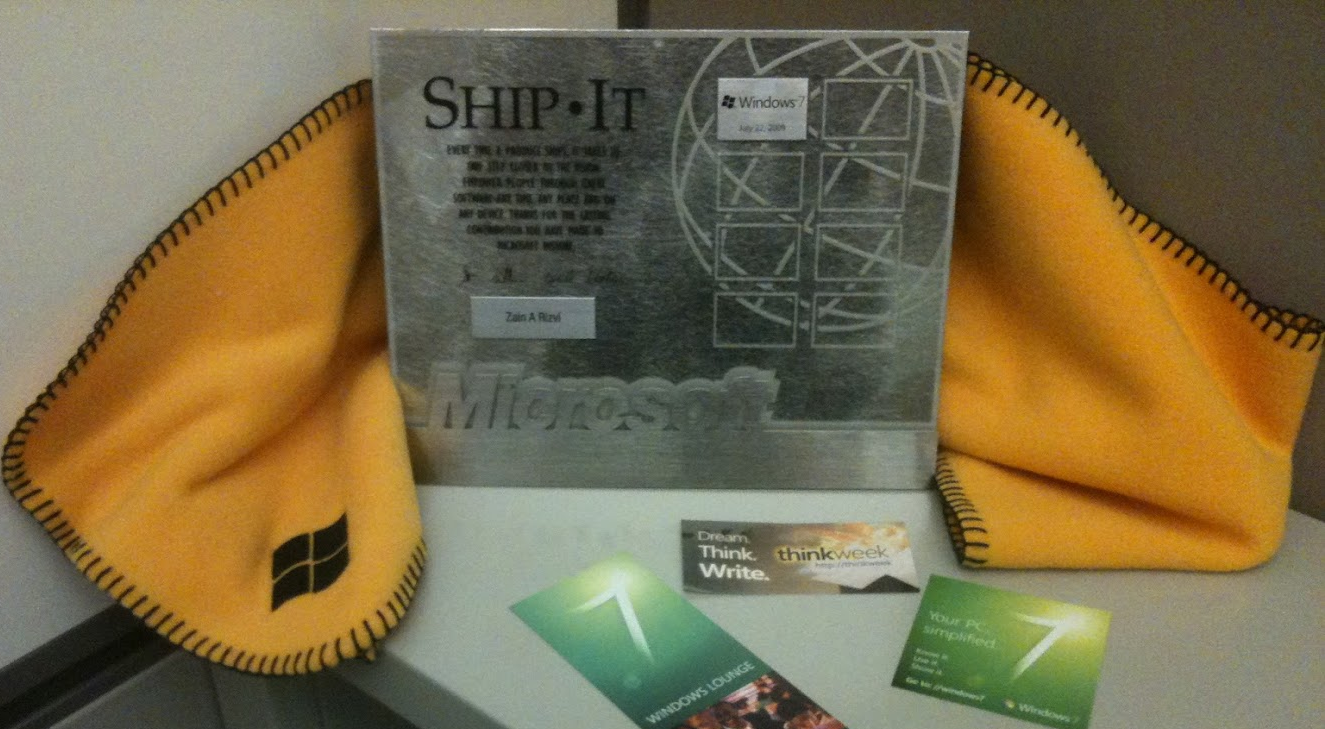

As I stood up from my desk, my eyes fell on my Ship-it plaque, congratulating me for helping release Windows 7. I had joined Microsoft a mere two weeks before it was released, a fresh college hire. There wasn’t a single character I had contributed to that code.

The plaque was a lie. Just like me.

My manager had booked a private conference room to share the results, far away from ears that might overhear anything said. Or begged. The long walk began, each step echoing down the corridor.

I racked my brains, grasping for an excuse to justify keeping my job. Instead my mind kept going back to the last bug I was supposed to fix. I’d spent all day failing to find the problem, finally giving in and asking a teammate for help. He found it in 10 minutes. I was way out of my league.

My boss must have seen it too, I bet that was why he assigned me, the kid, to help government auditors analyze our source code. Help them? I barely understood it myself! But this was more of a “people project.” If it didn’t require writing code, why waste real programmers on it? And so it came to me. I barely stayed afloat, constantly asking my manager for explanations and struggling to relay them to the auditors.

Yeah, I was doomed.

How would I tell my parents? Would I ever get another job? The only coding I did here was with an obsolete technology that no other company cared about; I didn’t even have the skills to land a new job.

What made me think I could work at Microsoft?

I reached the conference room, could I stall any longer? Huh, It’s the same room he interviewed me in two years ago. I doubt he remembers.

Okay, this is it. Deep breath, poker face on. No matter what, I wouldn’t let him see me sweat.

I stepped inside. Scott was sitting at the table, laptop carefully angled to hide the screen.

“Have a seat” he said, gesturing to his right. As I sat down, Scott looked straight at me. He opened his mouth to give me the news. But it wasn’t what I expected.

“Congratulations, you’ve been promoted”

Huh? No way I heard that right. Keep that poker face tight.

“Keep up the great work! Anything you’d like to ask?”

Wait but...when did I...what?

He hadn’t noticed? I wasn’t about to point out his mistake. Can’t let any surprise show.

“Great, thanks.” That was all I trusted myself to say.

I was safe. For now.

He’d catch on in a few months, I was sure. I couldn’t hide forever.

I spent the next few years preparing for that inevitable day, desperately trying to work on projects that could teach me the skills that would catch a recruiter’s eye. I had to become hireable.

I needed a stronger resume, with skills people cared about. I switched to a new team which built stuff for the cloud: Azure Web Apps. Companies love the cloud, right? Surely I’ll learn industry relevant skills there.

Fast forward four years: I still didn’t feel like I was anything special, yet I kept getting promoted. I kept fooling them somehow, the bureaucratic review process hiding my flaws. But something else also started happening, hinting that, just maybe, I wasn’t as clueless as I thought.

What changed?

People started coming to me for answers.

I still didn’t feel like I knew that much. I was just telling people about the stuff I’d worked on, occasionally pointing younger engineers towards tactics I had seen work well. That didn’t feel like anything original, but folks were finding it useful.

It got really weird when the more senior engineers started asking me about the code base. These were brilliant people who had often helped me over the years. Didn’t they already know everything?

I guess not, but they were still way above my league. It’s not like I knew enough to offer them real advice.

But still...my team seemed to think I was doing well. Would other companies think so too? Was I finally hireable? Only one way to find out: I started applying.

I couldn’t believe the results when multiple job offers came in. And one was from Google! I couldn’t pass that one up. I made the switch.

During orientation, Google spent a lot of time discussing Impostor Syndrome, the feeling of accomplished people belittling their own talents and constantly being terrified of being discovered as a fraud. That’s a thing?

“Raise your hand if you have this feeling” Hah, yeah right, and have me be the only one raising my...oh, wow, that’s a lot of hands. Mine joined the crowd.

As I started working, impostor syndrome came up constantly. It was mentioned at company meetings, folks made memes admitting to it. It was everywhere.

People freely admitted to not knowing stuff. Teammates admitted to not understanding the code, or having no idea how a tool worked. All the stuff I didn’t know, many others didn’t get either.

Seeing everyone admit their ignorance freed me from my own fear. Suddenly, feeling clueless seemed normal. It was a psychological quirk, not the truth.

My self-confidence grew. And gradually, without quite realizing it, something magical happened.

Impostor syndrome became a tool. I discovered the impostor’s advantage.

Did I notice feeling intimidated about asking a question? I started pushing myself to ask that question. Turns out other people had felt afraid as well, asking that question helped improve everyone’s understanding. When I started openly admitting to being unfamiliar with a tool or some code, my teammates felt like less of an impostor themselves. Their confidence went up. And they in turn became more likely to admit the same, creating a virtuous cycle boosting the entire team’s morale.

The impostor’s advantage was a super power.

And it offered new insights.

That feeling of being an impostor is your subconscious telling you something: It’s saying you’re about to push yourself past your comfort zone and into the growth zone. Now when an opportunity shows up and impostor syndrome starts twitching in the pit of my stomach, that’s a sign I should jump at it! This led me to take on bigger and more ambitious projects, without worrying about being exposed. Somehow I still delivered results, helped by the various people I was no longer afraid to reach out to.

Every project still started with the thought, “I have no idea what to do here.” But then I’d remind myself, “no one else does either.” That was a surprising lesson about the more senior positions: Their work is so valuable precisely because no one knows exactly what needs to be done. It’s ambiguous. And it requires people who can still push through the uncertainty and forge a path forward.

They embrace the impostor’s advantage.

Looking back, I realize now that in my early days I'd been evaluating myself with biased glasses. I was comparing myself to people much more senior than me. Of course there would be a skill gap. If one person understood something, I assumed everyone knew it. That was false. As the “systems grow it’s impossible for one person to keep it all in their head”[1]; each person just knew the areas they had personally worked on.

My biggest mistake: I didn’t value the soft skills I brought to the table. Fresh out of college I had taken a significant load off my manager's plate by being the main point of contact with auditors and other teams. The fact that I was not writing code made me think I wasn’t doing anything useful, when in fact the soft skill of being able to work with them was incredibly valuable to the team.

As I continue working and taking on bigger projects, I suspect impostor syndrome will never completely go away. But now I take that as a good thing. An advantage. It’s a sign that I’m growing and stretching myself past my comfort zone.

And in thost darkest moments, when self doubt is at its highest, I remind myself:

I haven’t been fired yet.

One of the ways I keep my impostor syndrome at bay is by interviewing regularly, trying to get at least one job offer every year.

This behavior led to me getting offers from Stripe and Facebook in addition to Google and Microsoft. It's not hard, it's just that no one tells you how to prepare for interviews the right way.

In the course Insider Advice on how to Pass FAANG Interviews I share the tactics I used to prepare and get those offers. Tech interviewing is a learnable skill and anyone can pick it up

Subscribe below to get the latest content whenever I publish anything. Or you could follow me on Twitter

[1] The Manager’s Path, by Camille Fournier